Persona Non Grata

How do we confront ourselves effectively, given our internal contradictions, unreliable perspectives, and fictionalized self?

We navigate between our reason, intuition, emotions, responsibilities, desires, and ideal self. Negotiating these competing selves—each with its own agenda—forces us to prioritize contradictions and live with dissonance, if only just enough to function. Adding to this, we have justified doubts that these facets of self are rather reliable, or at least our acquaintance with them is enough to know sometimes we can trust them and that sometimes we should not. If we are drunk, our reason is impaired. If we are hungry, our emotions and desires can overwhelm us like Mr. Hyde. If we are focused on responsibilities, we can easily present obligations as inanimate slave masters with ourself in a state of victimhood. If we are focused on our ideal self, we can make commitments and resolutions that are more ambitious than what goes with our usual habits. Then if we fatigue, we break those resolutions without much guilt since they were made in optimism. Worse still, we have imposed a narrative identity onto ourselves, requiring that each internal desire be twisted to align within its fictional constraints, within the arc of its invented plot.

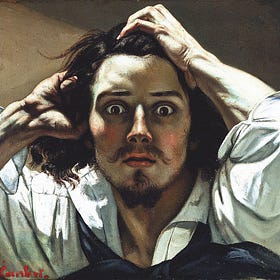

Literature offers us the concept of an unreliable narrator who gives their own account to the reader of the characters, dialogue, and action of the story, presenting “the facts”, emotional reactions, doubts, and evaluations as if they are rather objective. But there is inconsistency in how the voice presents their story, a bias, an irony that a Greek tragedy choir would expositionally sing for us if they were present. Without the choir, the reader must practice suspicion in order to understand the story. The reader has some clues and should therefore doubt the account. Michael Scott is not the “world’s best boss” as the mug he bought himself proclaims. Despite the introduction Nick Carraway offers to argue that he "reserves all judgments", his admiration for Gatsby or disdain for others is evident in the way he presents them. The delusions and distortions of subjectivity are clear of Edgar Allan Poe’s narrator who hears the heartbeat, Patrick Bateman as he goes on his killing spree, Humbert Humbert as he admires the shockingly young Lolita, and the dissociative narrator in Fight Club as we follow the development of his connections. To be skeptical of the narrator’s objectivity is essential to understand these stories. We know from these stories that it is prudent to practice some skepticism in the way reality is presented and how we present reality to ourself.

Yet in real life, we are our own main character, narrator, and interpreter in one. This interpretation work is difficult. Deciding when we should have skepticism, deciding when a little bad faith can make life bearable, deciding what to do with dissonance, deciding when to confront ourself is an intricate game we play.

We have experience with our various characteristics and have a familiarity perhaps better than anyone with judgments and outcomes that we could employ in order to know our true self. But we also have the ideal image that we rather accept, and the ability to filter our identity in order for that persona to be plausible. We exercise bad faith, which gives us the ability to be in denial when even a small thought or action does not align with the persona we have built. We accept dissonance, and make decisions despite its existence. We have fatigue, excuses, victimhood, alterity, the desire to save face. So we have some incentive to lie, most of all to ourself, that we are who we think we are. And we have a lifetime of experience in doing so.

Yet, as supposedly rational creatures, we perhaps should have some idea of who we are, some desire to confront our self, and some competencies to discern truth from narrative.

Those who know us best ought to be the second best option when searching for an expert on who we are. We could check with them when we doubt our self. We often do. But there are problems here as well for various reasons. First, it is through our lens that we inquire and receive feedback from the other. If we dare to ask, we already know the dynamic, so it is easy to craft the question to sound authentic but obtain the answer that aligns best with our desired answer. Or if we receive an answer that is not to our liking, we can make a critique of the other instead of accepting their message. Second, others often hesitate to tell us the truth—not out of malice, but to avoid discomfort, protect our ego, or preserve the relationship. It is rare for them to speak in honesty and present us with what is easily interpreted as ugliness. They can fear our reaction, even if we are sincere in our question, or perhaps they just prefer to avoid confrontation. Those closest to us know us well, which is the reason to seek their perspective, but part of what they know is our own ideal and how harshly we judge ourself in contrast to it, so they can lie in a desire to save us from the truth. They love us, so they as well likely have their own fictionalized version of us.

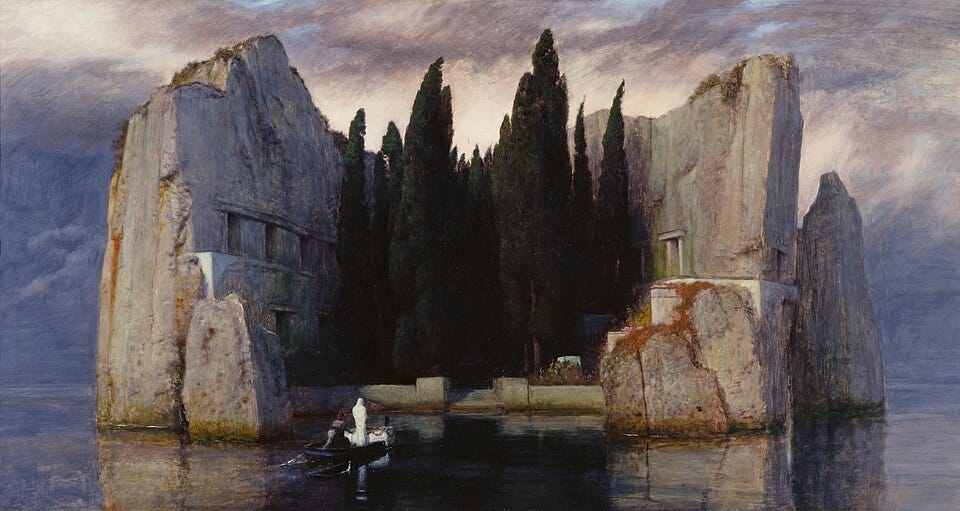

And so many of us live in a low simmering existential anxiety, with acute awareness that we maintain a belief, with varying levels of inadequate faithfulness, in our flimsily crafted persona. We introduce it to acquaintances, we promote it as our story, we protect it to avoid pain. We romanticize it for beauty, emphasize it for interest, radicalize it for drama. But there is what we say we are and there is what we do. Our values and actions sometimes are aligned, and other times are easily ignored or forgotten for our own soft comfort. Otherwise life would be ugly. We try to avoid confronting the portrait we have stored in the Wildesque attic of our mind.

No one is exempt. Especially philosophers, who claim the title of at once the most revered and the most ridiculous occupation. We are all amateur philosophers when we practice critical thinking, ask questions about reality and meaning, and confront ourself. In philosophical practice, we do this work deliberately. We compose arguments and critique them, dissolving the illusion that an idea is brilliant and beautiful just because we birthed it, building competencies to better think clearly, and exploring what it is to be human and navigate our dissonance.

The strength of a person's spirit would then be measured by how much 'truth' he could tolerate, or more precisely, to what extent he needs to have it diluted, disguised, sweetened, muted, falsified.

― Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

If we are to live with greater clarity and integrity, we must learn to examine the stories we tell ourselves as well as the narrator we trust to tell them. Philosophy offers not answers but methods: ways of questioning, tools for untangling contradictions, and the courage to face uncomfortable truths. Working with a philosophy practitioner offers a space for this kind of inquiry. It is a disciplined conversation where critical thinking meets lived experience: where we practice confronting our assumptions, examining our values, and refining the lens through which we interpret ourselves and the world. If you are ready to engage more honestly with your inner narrator and the persona you have constructed, philosophical practice offers both the tools and the challenge. To start this dialogue with self and schedule a session, feel free to write to me directly.

Ontological Vertigo

Vertigo is a disoriented sense of groundlessness. It literally refers to the symptom of dizziness or spinning. But the idea of panic when we are unsure of our stability grounded on something concrete metaphorically describes when we are lost. Lost in our humanity, between dogmatic…

Outrospection

When we have conflicts or problems, we try methods of introspection, which can easily move towards an examination of what is right, what is our motive, what is our purpose. We learn to question ourself because as a child we were told by our parents that we do not always get what we want, that we are sometimes in error in our…