Dismissive Justification

-You don’t seem like you are enjoying this. Do you want to continue? I asked a friend.

-I’m excited, it just doesn’t seem so because I have a monotone voice, she replied.

This conversation interests me because of the functioning of her argument. Yes, she is aware that her voice betrays her. Yet, because she knows this, she dismisses the provocation to think about her engagement, state, or agency. She has a rational explanation to the perception, so therefore she does not reflect on whether the tone is a characteristic in itself or a symptom of something more essential to her being. Maybe she thinks her attitude towards life is normal. Maybe she thinks I have a prejudice towards her because I am stuck on the superficial impression her tone of voice gives. I find her interesting because of what her tone of voice along with other verbal and non verbal cues reveal. I find her even more interesting because she believes she has self knowledge with this statement, yet she stops herself from exploring her interesting, deeper character since she has her rationale.

We tend to seek explanations, but once we find one that seems reasonable, become satisfied with having solved the puzzle and take no interest in critiquing, deepening, exploring, or looking further.

In trying to find explanations, we practice being curious, rational creatures who want to understand a problem and the world around us. In pointing a finger, we decide on a hypothesis and propose it to ourself and those around us. With some answer that works in our scheme of thinking, we are happy with the job done and we close the book on the issue. The satisfaction we get with our acceptance of this conclusion stops the thinking. No more hypotheses, no more curiosity, no more effort to explore other options, no more composition to try different perspectives. We avoid testing the hypothesis beyond declaring it out loud to see if it sounds good. We suspend any self critique out of laziness, lack of habit, not seeing any value in the work, trust in our own thinking, or not having a model of critical thinking to consider self critique a normal part of thinking work. We share our hypothesis to those who listen, in social conversation, believing in the hypothesis as if it is some revelation of truth we can offer others as a gift. We are happy when they recognize and accept the beauty of our thinking, or offended when they challenge the idea or offer a different explanation, as if to critique our idea is to critique our very being. We rarely take a moment to consider the implications of the possible explanations unless they are practical. We have an answer—we can move on.

This dismissive justification is part of social training, as it works well in relational situations to be nice. Look at how easy it is to say yes to a social invitation:

-The party is on Saturday–we hope you will join us.

-I would love to! Thank you for inviting us. I remember how fun last year’s party was.

Yet when the answer is no, we avoid saying the word directly by drowning the host in justifications:

-I’m sorry, but we don’t currently have a babysitter. The grandparents are out of town and someone has to drive the kids to practice in the morning.

-Oh no! I have to fly to New York for a work event that weekend.

-I hope your party was fun. So sad I missed it. Unfortunately I was feeling sick and didn’t want to be contagious. What a nasty cold going around right now!

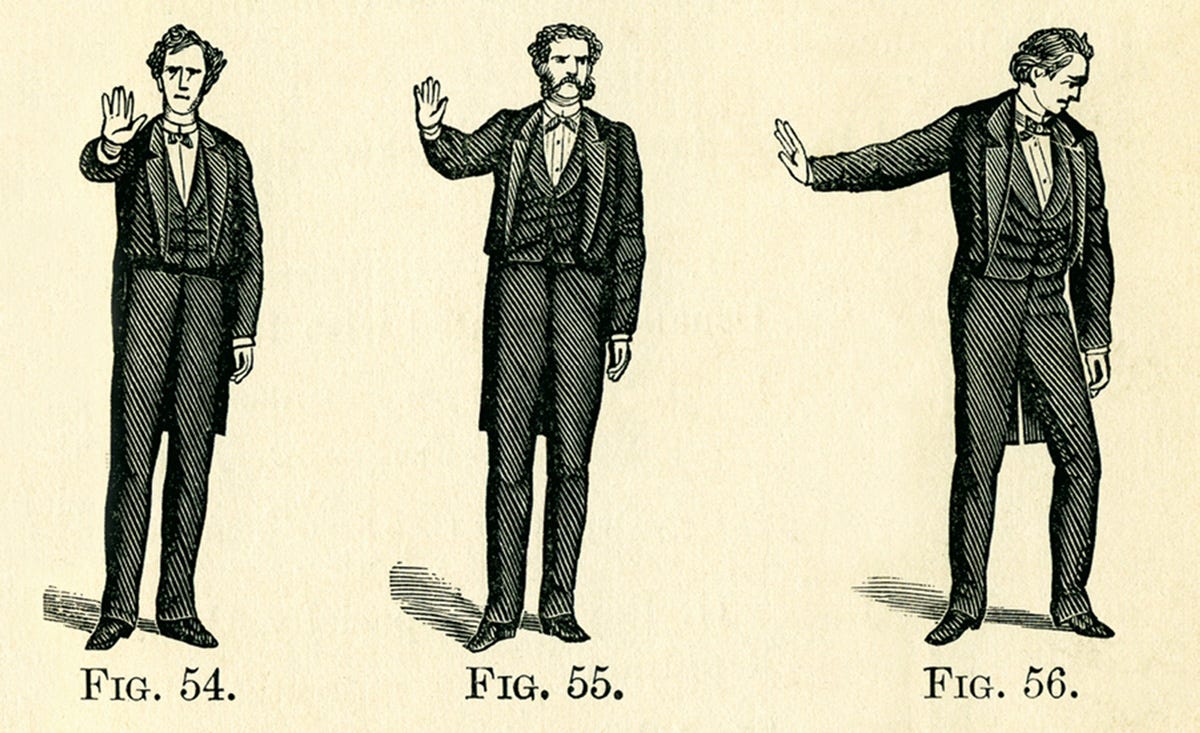

The justifications are sincerely offered, dramatically performed to convey the heaviest of regrets, and detailed with responsibilities that of course should take priority. The answerer makes a deliberate theatre of the answer to express that they would otherwise love to come. The host waits to interpret instead of receiving a direct yes. By the arrival of the no, the subject of the conversation may have already evolved into the territory of the excuse to distract from the disappointment of the denial. And everyone has the answer, so no need to continue. This social mechanism has corrupted our thinking, as we let the method of dismissal invade the way we approach problems to solve. We are satisfied with a little justification, no matter how weak or in bad faith composed.

The news is currently full of headlines trying to make sense of the 2024 US elections. The polls showed an evenly contested race, with swing states within the margin of error, too close to call. The results, on the contrary, are definitive. Now the theories abound to explain the outcome: Biden’s late dropout, the gender divide, the economy or inflation, a lack of articulated platform, a global trend of divisiveness, etc. Pundits and pollsters pick their favorite and treat it like an accepted premise for the next round of elections. Political strategists study them for practical lessons and try to adopt the effective moves to build the hopes of the next potential candidates. Will we voters learn anything?

In critical thinking exercises, we ask for three different positions and arguments. This challenges the thinker to play with perspectives they do not hold, to try building arguments that are foreign to them, and to not rely on the justification we inherited or created as we grew up to understand the world. What is most interesting in facilitating this work, is that the thinker usually enjoys the beauty of the second or third position the most, despite how easily they write the first position. We give space in thinking work. We accept the first argument as a fallible, only an option of many, open to critique, subject to examination. We consider the thinker as agile, available, capable of thinking beyond what they know and creating argumentation to justify different positions. We do not accept the first argument and dismiss the desire to explore more.